It Starts With You

It Starts With You April 14, 2025 The communities we dream of — where everyone belongs, where each person is treated with dignity, where kindness and justice shape daily life — don’t just happen. They are created. They are built, moment by moment, by people who choose to live their values out loud — in their workplaces, their neighborhoods, their schools, and their homes. At the Wassmuth Center for Human Rights, we believe in the power of ordinary people to do extraordinary things when they commit to cultivating communities rooted in human rights. We imagine an Idaho and a world where kindness is non-negotiable, inclusion is intentional, and every person’s humanity is honored. But creating that kind of world takes more than good intentions. It takes learning. It takes courage. It takes practice. That’s why we offer programs like our Human Rights Certificate — an online learning experience designed to help people reflect deeply, act intentionally, and lead with heart. Through six engaging modules, participants explore what it means to lead with intention, respond to the needs of their communities, and foster environments where all are treated with dignity and respect. Whether you’re seeking to strengthen your leadership, create a more welcoming workplace, or simply live with greater awareness and compassion, this course offers tools, insights, and inspiration to guide you. The future we long for is shaped by the choices we make today. We invite you to join us to learn, to reflect, and to be part of building a more just, joyful, and inclusive world. It starts here. It starts with us. It starts with you.

A Place to Call Home

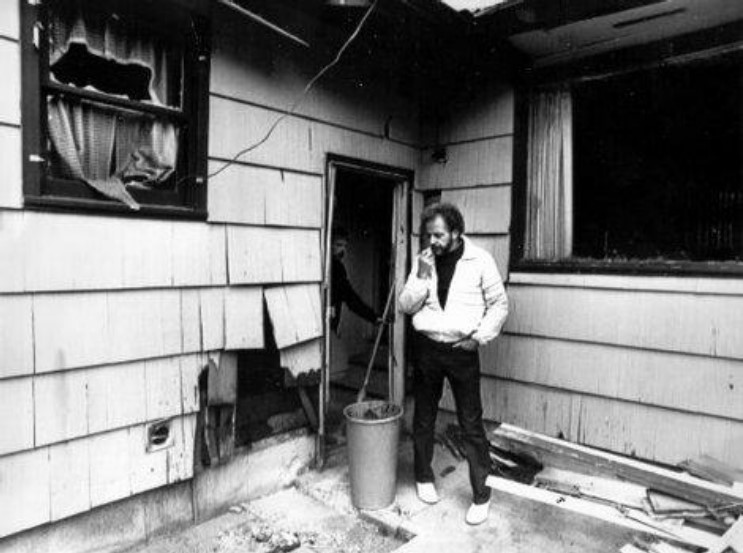

A Place to Call Home April 21, 2025 As April brings warmer days, blooming flowers, and green leaves, many of us head back outside—on bicycles, in gardens, and on trails—after a long winter indoors. Idaho offers so many beautiful outdoor spaces to enjoy. But for many of our neighbors, spring marks the return of another season without stable housing. While the cold may ease, heat and smoke will soon bring new challenges. April is Fair Housing Month—a time to reflect on one of our most basic needs: a home. The most recent estimate is that at least 2,750 Idahoans are unhoused. An additional 9,500 Idahoans received some kind of housing assistance in 2024. The paths to becoming unhoused are varied, and the solutions are complex, personal, and structural. Many Idahoans live just one paycheck or an unexpected medical bill away from losing their houses. Waitlists for affordable housing often exceed 300 families, with some people waiting years for a chance at securing an affordable place. Communities across Idaho and the nation are exploring various strategies to address housing shortages and support those who don’t have stable housing. The Fair Housing Act of 1968, established to counter discriminatory practices like redlining, prohibits housing discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, disability, or familial status. This landmark legislation provides crucial legal protections, but ongoing housing challenges reveal how much work remains to ensure that all people have equitable access to safe and affordable housing. While there is broad agreement that the crisis deserves urgent attention, many people are reluctant to support potential solutions—such as increased housing density—in their own neighborhoods. As systemic efforts continue, each of us can reflect on our own assumptions about people who are unhoused or in vulnerable circumstances. A resident at a shelter in Boise said it best: “People look down on me, but my worth and value is not based on my circumstances.” As we work to build communities rooted in dignity and belonging, let’s ensure our welcome includes those living on the uncomfortable margins. Let’s not just view housing instability as a problem to solve but see the people—parents, children, veterans, fellow community members—all with names, stories, and the right to be treated with compassion.

Keep Showing Up

Keep Showing Up May 5, 2025 As we step into May, many of us feel the weight of what it means to live through another chapter of historic and unprecedented times. The fatigue is real. We long for calm, for clarity, for something steady beneath our feet. And yet—while we don’t get to choose the times we live in, we do get to choose how we respond. In a moment when political division runs deep and economic uncertainty touches nearly every corner of life, it can feel tempting to withdraw and turn inward. But these are not times to retreat. These are times that call for something bolder: showing up for one another with hope, with courage, and with belief in a brighter future for all of us. At the Wassmuth Center, we draw strength from the many ways people across Idaho continue to show up. During Idaho Gives last week, more than 13,500 Idahoans gave what they could—money, time, encouragement—to support nonprofits working every day to meet urgent needs and build a more just, compassionate future. That’s not just generosity; it’s civic action. Every donation, every volunteer hour, every shared conversation speaks clearly about the kind of world we want to live in and the legacy we hope to leave. Whether you’re donating, organizing, mentoring, making art, discussing books, attending town hall meetings, or talking with your kids about values at the dinner table, you are part of the work. You are creating ripples of impact that move outward in powerful, often unseen ways. But grassroots efforts grow. They connect. And together, they shape a future that is more fair, more generous, more human. So let’s keep showing up—for each other, for our communities, and for the future we still believe is possible. Join us at the Center this month for learning, for conversation, for connection. Let’s stay rooted in joy, keep choosing courage, and move forward together.

Hope’s Defiance

Hope’s Defiance May 12, 2025 In a world increasingly fractured by injustice, we need more than comfort. We need hope—hope that pushes back against darkness, shines through the cracks, and calls us to act. This can feel difficult when democratic norms are eroding, books are being banned, hate-fueled violence is rising, and basic rights are under threat. But in the face of these challenges, we must turn to what has always sustained movements for justice. Not despair, but imagination. Notsilence, but expression. Not fear, but defiant hope. Art has long played a vital role in this work. In moments of crisis, art helps us see clearly, feel deeply, and envision a future beyond the fractures of the present. At the Wassmuth Center, we are surrounded by 28 human rights-themed artworks created by artists from diverse backgrounds. These pieces offer more than beauty. They speak truth, stir conscience, and compel us toward action. One powerful example is Hope’s Defiance, a mosaic by local artist Reham Aarti. In it, Hope is not passive or gentle. She stands tall on a pile of books—symbols of knowledge and community—and pushes back against darkness, cracking it open to let light through. Especially now in times of censorship, this image reminds us that learning and truth-telling are essential forms of resistance. Mosaics are made from what’s been broken. And today, as systems crack under the weight of injustice—from attacks on voting rights to violence against marginalized communities—we are called to gather the pieces and build anew. This is the work of championing human rights. That’s why Hope’s Defiance matters. Because sometimes, hope rises from the rubble and is pieced together with courage. Like a mosaic, it is formed from what has been shattered, reassembled into something stronger and more beautiful than before. This is not naive optimism. It is a grounded, determined response to all that threatens to divide and diminish us. Hope is a commitment: to see clearly, act defiantly, and move forward together. We invite you to visit Hope’s Defiance and the other remarkable works at the Center. Please also join us for programs that foster understanding, amplify community voices, and inspire meaningful action. Together, we can shape a future rooted in dignity, built with courage, and powered by defiant hope.

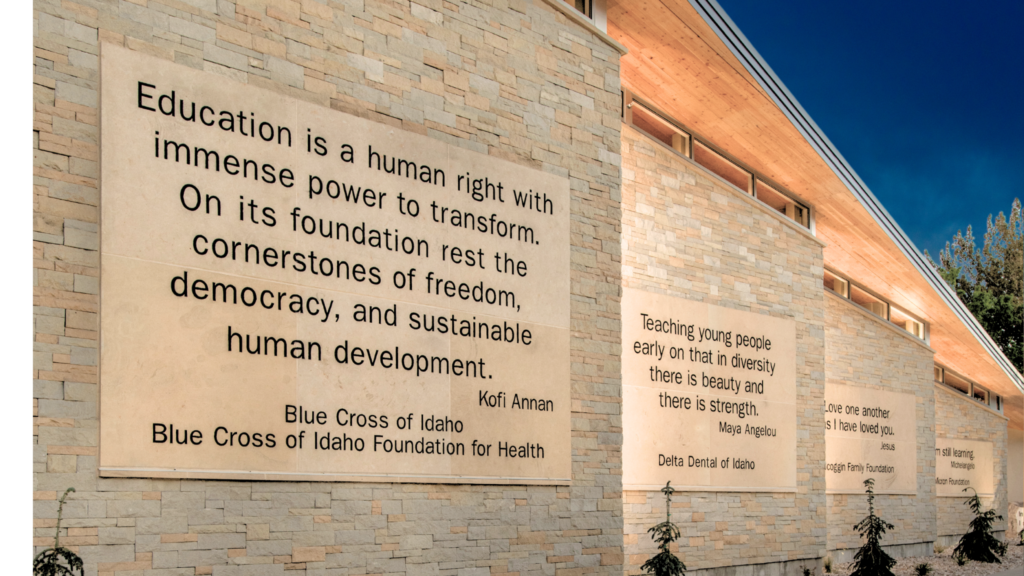

Education is a Human Right

Education is a Human Right: Learning from Cambodia At the Wassmuth Center for Human Rights, we believe education is a fundamental human right. Education shapes communities, advances dignity, and ensures that history’s hardest lessons are never forgotten. This conviction led us to Cambodia over spring break, where we guided a group of Idaho high school students on a journey to learn about the country’s history, culture, and resilience. This was also an opportunity to witness how a nation rebuilds after enduring one of the most devastating genocides of the twentieth century – brick by brick, classroom by classroom, student by student. The Cambodian genocide nearly erased an entire generation of scholars, teachers, and students. Schools were dismantled. Books were burned. Knowledge was silenced. In the years since, Cambodia has faced the extraordinary challenge of reconstructing an education system from the ground up. Today, education in Cambodia is not only about learning—it is an act of resilience and hope. For our students, this experience far surpassed studying human rights violations in a textbook. We walked through genocide memorials in Phnom Penh, stood in the haunting silence of the Killing Fields, and looked into the eyes of survivors who continue to fight for a better future. The students wrestled with difficult but essential questions: How do we ensure education is never used as a tool of oppression? How do we protect the right to learn – both globally and in our local communities? One of the most transformative moments of our trip happened in a rural schoolyard outside Siem Reap. There, we delivered 208 bicycles and backpacks to children whose futures hinge on something as simple as a way to get to school. In Cambodia, access to education often depends on distance—if a child can’t walk there, they simply can’t go. Therefore, a bicycle is more than transportation; it is a bridge to learning, a tool of empowerment, and a symbol of possibility. As we shared a meal, planted trees, played games, and spoke with students and teachers, we saw firsthand the impact of this simple but life-changing gift. One Boise student reflected, “I knew that education could change lives, but I had never seen it so clearly before. Watching these kids climb onto their bikes, knowing they now had a way to reach school, made me realize how much I take for granted and how hard I want to work to make education accessible for more kids.” Back home, at the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial, the genocide wall stands as a solemn reminder of the devastating cost of hatred, silence, and indifference. The names etched there are not just history – they are a warning. They compel us to recognize that injustice is not confined to the past. It is a continuous challenge that demands our vigilance. And education remains one of the most powerful tools we have to build a future where such atrocities are never repeated. The lessons we bring home from Cambodia reinforce this truth. We are challenged to ask: How do we protect education and human rights in our local communities? How do we ensure that all children, no matter where they live, have the opportunity to learn and thrive? This journey is only the beginning. We invite you to join us. Together, we can safeguard education as a human right – in Cambodia, in Idaho, and in every place children dream of a better future. Be a Part of Building Our Future The Wassmuth Center for Human Rights is 100% dependent on donations. We need your help to continue the valuable work being done in classrooms and communities throughout the state. Ways to Donate

Living into the Promise of America

This official retreat from our founding ideals not only undermines global human rights—it also reflects a broader erosion of democratic values, both abroad and at home.

Everyone is Welcome Here

This moment is about more than a sign—it is a reflection of who we are and the future we are building together.

The Hidden History of Human Rights in Idaho

Beneath the surface of our history are extraordinary stories of communities that refused to let hate have the final word.